Boston’s Black Hairdressers: Beauty Culture in the 1920 Women’s Voter Registers

by Anna Boyles

Boston women’s voter registrations from 1920 reveal that a number of women migrated from southern states to make neighborhoods such as the South End and Lower Roxbury their home. Looking further, a pattern emerges. Many of these southern women reported to voter registration clerks that they were occupied as hairdressers. Furthermore, their census records indicate that these southern-born hairdressers were Black or mixed-race persons. What led to this concentration of Black southern women working as hairdressers after migrating to Boston?

From 1914 to 1920, roughly 30,000 to 50,000 Black Southerners migrated from southern states, many attracted to the industrial jobs available in northern cities like Boston. This historical shift in the Black population of the U.S. is known as the Great Migration. While some fled the South due to racial terror and Jim Crow policies, many were enticed by industrial jobs offered in northern cities. Black men were able to secure such jobs in the north, but Black women remained restricted primarily to employment in domestic service. Unfortunately, domestic workers faced long hours, low wages, little control over work routine, and no room for advancement. It is no surprise, therefore, that Black women sought employment elsewhere. According to sociologist Robert L. Boyd, Black women succeeded in careers in hairdressing and beauty culture during the Great Migration for several reasons.

First, beauty was a relatively easy field to enter; training was available in some public schools as well as local beauty colleges. In addition, women could run salons out of their own homes. Beauty jobs offered more flexibility, meaning that women could balance family responsibilities and a wage-earning job. Black women were especially knowledgeable in the distinct requirements of Black hair care. This allowed them to compete successfully against those untrained in cutting, styling, and caring for Black hair. Jobs in the beauty field provided room for growth. One could expand from a home shop to a salon to maybe one day a beauty school or manufacturing enterprise for beauty products. This meant that some women in the beauty industry could climb the social and economic ladder. Some may have been inspired to enter the beauty field after seeing the success of Madam C.J. Walker, Black entrepreneur and founder of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Born in Louisiana to her formerly enslaved parents, Walker moved to St. Louis and developed hair products and beauty schools for Black women. She is often credited as being the first Black self-made millionaire.

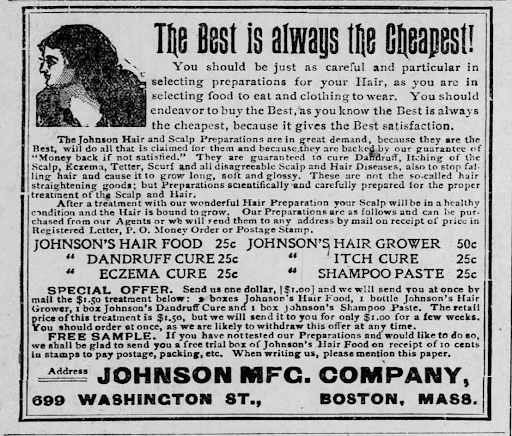

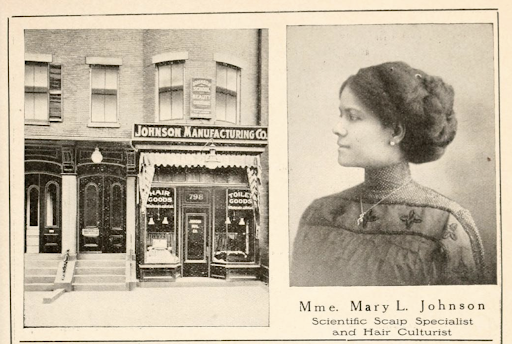

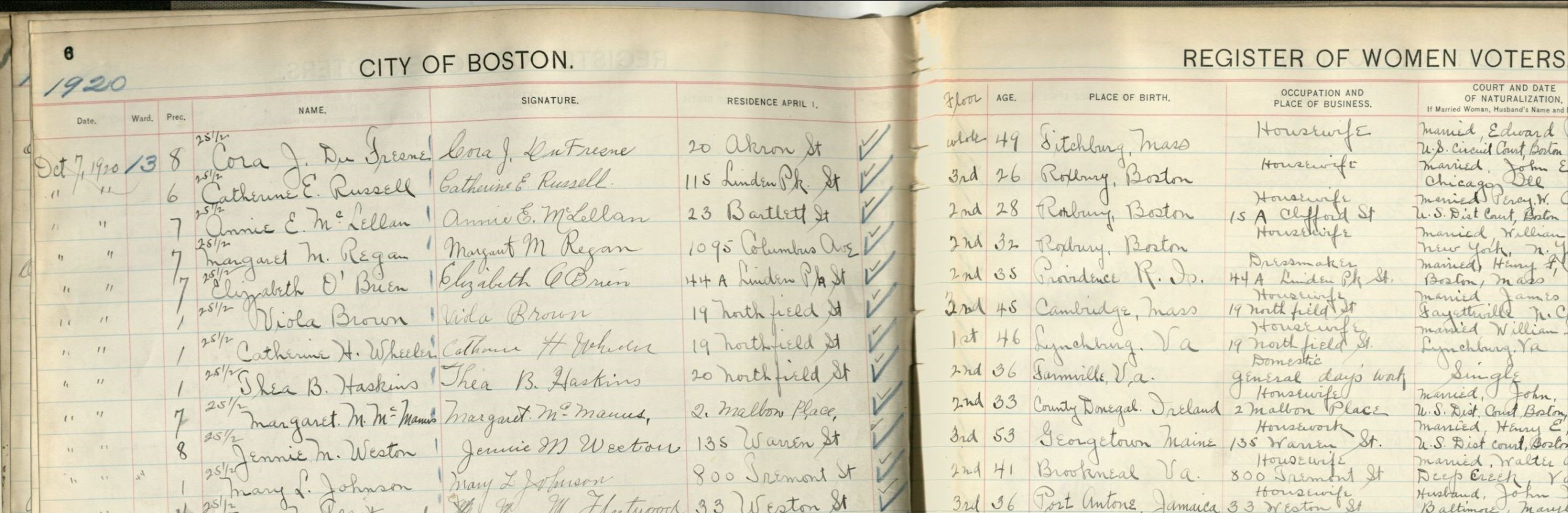

One new Boston voter who took advantage of the opportunities of hairdressing was Mary L. Johnson. Born in Virginia around 1880, Johnson married a fellow southern-born man, Dr. W. Alexander Johson, in 1896 in Boston. Together, they began selling Johnson’s Hair Food in 1900, which could be bought from agents or ordered through the mail. She advertised her products across the country, including in Alabama, Virginia, Missouri, and Colorado. In addition, Boston residents and visitors could purchase these hair and scalp products at Johnson’s Hair Store on Shawmut Avenue. Johnson would go on to open a beauty school, with two locations listed in the 1920 Boston Register and Business Directory: 800 Tremont Street and 561 Shawmut Avenue.

It is unclear, then, why Boston city clerks recorded Mary L. Johnson’s occupation as “housewife” when she registered to vote in 1920.

The data recorded in the registers was impacted by what each voter registration clerk asked women and how they chose to record their answers. We have found clerks often choosing to record a woman’s occupations as housewife when she, in fact, holds a job, like in the case of Mary L. Johnson. In some instances, we have even found clerks appearing to be corrected by women registering to vote. In some entries, “housewife” had been recorded as the occupation before being struck out and another job being written next to it. You can discover more working women and southern women in the transcribed records of Wards 1, 6, 8, and 13

Read more:

- Tiffany M. Gill, Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry

- Robert L. Boyd, The Great Migration to the North and the Rise of Ethnic Niches for African American Women in Beauty Culture and Hairdressing, 1910-1920

- Anthony W. Neal, A Noble History, Bay State Banner

- Indiana Historical Society, Madam C.J. Walker

Anna Boyles is a dual-degree student in History and Archives Management at Simmons University.